Learning From History: Gulf Property Market Cycles – Catalysts And Consequences

The Gulf is far from immune

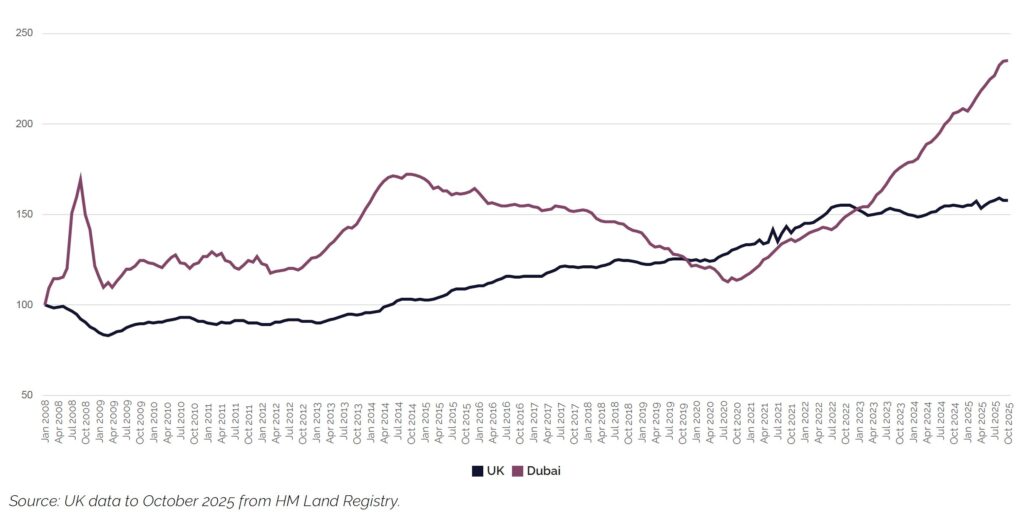

Everyone knows that housing and commercial property prices move in cycles. The pattern of a long-sustained build-up in asset prices followed by a sudden decline has been observed in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries for decades. It is also known that real estate returns are generally more stable in the years between peaks and troughs. Not all cycles, however, are equally severe, nor are markets equally volatile. For example, comparing what has happened in Dubai since 2021 with UK average prices clearly indicates how much more volatile this Gulf market has been. And, of course, Dubai has seen much more impressive house price growth in recent years: when both markets are indexed to January 2008 = 100, UK prices stand at 158.3 while Dubai reaches 233.7.

Investors, then, have every reason to take a close interest in what causes property prices to deviate from a steady growth pattern. So what does drive these cycles?

UK vs Dubai house prices in local currency

What drives real estate cycles?

on developed markets, the USA and UK in particular. The first explanation focuses on the link between infrastructure spending in the wider economy, generalised inflation, and the dominance of speculative activity in the economy as a whole. This is a line of reasoning often credited to Nikolai Kondratieff, a Russian economist working in the early years of last century.[1] His argument has been extended to suggest that periods of negative returns in the 20th century were caused by excessive levels of new construction, induced by an unusual rise in Net Operating Income (NOI) and rental yields, which in turn was the result of an inflation spike in the general level of prices.[2] These boom-busts operate over a very long time period – some 50 to 60 years – although some analysts suggest cycles of up to a century. However, the evidence from the 21st century is scarcely supportive of this argument: inflation was not running at exceptionally high levels prior to the Great Recession, nor was it before the pandemic, which anyway induced diametrically opposite trajectories for property prices in the UK and Dubai. But even if opinion is divided over their causes, that these long-term cycles exist is largely not in doubt – but they are not the only ones.

A second school of thought points to long-term, specifically real estate, cycles. Homer Hoyt’s initial empirical work referenced a century of land values, rents and other real estate indicators in Chicago.[3] The idea of an 18-year real estate cycle revolving around land prices also appeared in the work of Roy Wenzlick, writing at the same time. He pioneered the formalisation of a national real estate cycle driven by overbuilding and credit expansion.[4] More recent interpretations of the 18-year cycle owe far more to Wenzlick’s predictive framework than to Hoyt’s historical analysis.[5] Hoyt himself lost faith in his own idea, suggesting that society had outgrown it, but the notion of Government regulation triumphing over boom and bust has now in turn been overturned by the experience of successive real estate crises worldwide. The relative stability that postwar institutional investors experienced turned out to be an anomaly, not a new pattern of persistent low volatility, still less the ‘banishing of boom and bust’ rashly promised by one UK Chancellor of the Exchequer.[6]

A more refined view of the original 18-year cycle now focuses on credit expansion (and then contraction) at a national level, often accompanied by regulatory tightening and loosening that, with poor timing, frequently exacerbates cyclicality instead of curbing it.[7] Solid empirical evidence shows that current account deficits, real interest rates, and per capita GDP growth were the main drivers of real estate appreciation in OECD countries prior to the Great Recession of 2007–10, with particular emphasis on the influence of mortgage rates.[8] That emphasis is explained by the fact that economies where households carry a high level of debt, most of which is at variable rates, were always likely to be very sensitive to short-term adjustment in interest rate levels.[9] Some economists forecast the catastrophic outcome of the Great Recession that was to flow from these policy settings very clearly.[10] Other cyclical factors include institutional innovation (and then failure), demographics, and construction booms overshooting and creating real estate beyond current requirements. The importance of geopolitical crises standing behind many of these economic trends has now been widely recognised.[11]

Each of these long-term real estate cycles has been characterised by expansion, including the creation of new developers, overbuilding and rapid and often poorly regulated lending, a sudden crisis, and then a gradual recovery as absorption rates increase, followed by renewed expansion. It is also important to recognise that how quickly house prices rise during expansion periods is a key factor in determining the extent of subsequent price falls. Whether each long cycle peaks at higher levels of leverage, financial engineering and institutional complexity than its predecessor, as Kaiser thought, or whether peaks can be measured more accurately by ‘bubble ratios’ of house prices (in particular) to income and other assets, is now much more a subject of debate than whether these cycles exist. Questions over whether affordability can be maintained indefinitely at such low levels are certainly a feature of the modern version of this analysis.

Finally, most recent commentators tend towards the view that construction levels may act as leading indicators of short-term, pipeline-induced changes in price levels. This may be useful in managing real estate portfolios, in the timing of purchases and sales, but not in the top-tier strategic question of how much to allocate to real estate versus other assets, bonds in particular. Short-term, supply–demand dynamics do naturally play a significant role, particularly in fast-growing markets such as Dubai. These movements are not ‘cycles’ in the classical theoretical sense, but they arise from the interaction of construction pipelines, absorption rates, and shifts in sentiment and liquidity. Because supply can come to market quickly and demand can adjust just as rapidly, these short-term oscillations often appear as mini-cycles within the broader long-wave pattern. They matter less for structural analysis but are highly relevant for tactical decisions on timing, pricing, and portfolio rotation.[12]

It is also important to recognise that the timing and extent of real estate cycles have serious consequences for the rest of the economy. Economic downturns are significantly deeper and more prolonged when housing contractions follow a preceding boom expansion.[13] Commentators in developed economies have pointed to the likely deepening of this tendency in a world where real estate values no longer hinge on industrial output as they did in the past, but are – alongside the financial sector – arguably the most important driver of developed economies as a whole.[14] Previous experience whereby rapid falls in real estate market values have almost inevitably followed the collapse of equity prices, often with significant lags, may not now be a reliable guide to how future real estate downturns will play out.

“Dubai real estate moves in cycles like any global market, but what differentiates it is the speed and transparency of correction. Periods of rapid capital inflow and price growth are typically followed by rationalisation, stronger regulation, and a more resilient recovery. Those who understand the cycle rather than react emotionally to it are the ones who consistently create long-term value in Dubai.”

Zacky Sajjad

Director, Business Development and Client Relations

What are the lessons for the Gulf?

Gulf markets have also tracked these components of change: the construction surge in Dubai between 2005 and 2008, the 2014–16 oil price linked correction, and the post pandemic divergence in pricing – Dubai residential prices have continued to rise when other markets have seen subdued price growth or even a reversal. It is tempting to conclude that Gulf markets are still structurally more volatile, more cyclical, and more sensitive to macro-financial and geopolitical catalysts than mature OECD markets. Investors can therefore always benefit from acting on the information provided by effective early-warning systems. One of the most important components of such a system is the way in which land price trends act as a leading indicator of market corrections in the secondary market.[15] Access to high-quality amalgamated land price data at a jurisdictional level, such as an Emirate or a Gulf country, therefore places real estate advisers such as Cavendish Maxwell in an advantageous position to advise their clients of cyclical trends in the real estate market as a whole.

The early warning systems advisers build also incorporate other leading indicators. These include trends in the extent of credit growth, especially given the fact that markets which still provide the kind of returns that the Gulf has even recently generated are more susceptible to forward linkages between credit and house prices than in the opposite direction.[16] Trends in debt-service-to-income (DSTI) and loan-to-value (LTV) ratios are therefore proven indicators of future market direction,[17] as is the long-term occupancy average (LTOA) for commercial real estate. All of these have proven worth in predicting the timing and scale of market corrections.[18] This may be especially so when mortgage markets are accelerating in market penetration, including credit available to property owners who are engaged in leasing out their properties, competing with home owners.[19] The importance of these indicators is redoubled when purely time series econometric analysis of Dubai house price data appears to suggest that market conditions have been relatively benign.[20] The usefulness of such research is always critically dependent on exactly when the time series utilised begins and ends, and it must always be balanced by modelling based on leading indicators.

Conclusions

Real estate markets are always subject to cycles and Gulf markets are no exception. The importance of understanding and acting appropriately on information about real estate cycles is undeniable. It is therefore the role of advisers to deliver clear and unbiased advice to their clients in respect of real estate cycles. Despite extensive research over many decades, disagreement among academics and analysts still exists on the exact cause of real estate cycles. However, there is widespread agreement on key leading indicators. In Gulf markets that have proved both highly profitable but also volatile, this is therefore advice of an especially valuable kind. To conclude with the wise words of Robert Kaiser, ‘Even for those who come to believe there may again be a period of boom/bust for real estate (once another inflation spike occurs), industry peer pressure will be a difficult thing to act against.’ [21]

[1] Garvy, G. (2025). Kondratieff’s theory of long cycles. In Readings in Business Cycles and National Income. Routledge, pp. 438–466. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003679981-37/kondratieff-theory-long-cycles-george-garvy.

[2] Kaiser, R. (1997). The Long Cycle in Real Estate. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14(3), 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1997.12090911.

[3] Hoyt, H. (1933) One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago: The Relationship of the Growth of Chicago to the Rise of Its Land Values, 1830–1933. 1st edition. Chicago, Chicago University Press.

[4] Wenzlick, R. (1933). The problem of analyzing local real estate cycles. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 28(181A), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/2282243.

[5] Harrison, F. (2006). Boom/bust: House prices, banking and the depression of 2010. Shepheard‑Walwyn.

[6] Pickard, J. (2008, November 21). Gordon Brown “apologises” for claiming to have ended boom and bust. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/ba54c2c8-7a74-355a-9ede-52ef78e9a558.

[7] Albuquerque, B., Cerutti, E., Kido, Y., & Varghese, R. (2026). Not all Housing Cycles are Created Equal: Macroeconomic Consequences of Housing Booms. Journal of International Money and Finance,

161, 103496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2025.103496

[8] Almeida, R. P. (2025). Cycles, Trends, Disruptions: Real Estate Centrality on the Global Financial Crisis, COVID-19 Pandemic, and New Techno-Economic Paradigm. Real Estate, 2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/realestate2010001

[9] Renaud, B. (1997). The 1985 to 1994 Global Real Estate Cycle: An Overview. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 5(1), 13–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1997.12090058

[10] Rajan, R. G. (2006). Has finance made the world riskier?. European financial management, 12(4), 499–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-036X.2006.00330.x.

[11] Ulupinar, B., & Camyar, I. (2025). Geopolitics and investment cycles in the United States. Economics Bulletin, 45(2), 1013–1028. http://www.accessecon.com/Pubs/EB/2025/Volume45/EB-25-V45-I2-P88.pdf

[12] Mueller, G. (2001). Predicting Long-Term Trends and Market Cycles in Commercial Real Estate. Working Paper 388. https://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/388.pdf.

[13] Sarto, A. (2024). The Channels of Amplification: Dissecting the Credit Boom that Led to the Global Financial Crisis. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=4806247.SSRN.

[14] Hofman, A. & Aalbers, M. B. (2019). A finance-and real estate-driven regime in the United Kingdom. Geoforum, 100, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.014

[15] Fitzgerald, M., Hansen, D. J., McIntosh, W., & Slade, B. A. (2020). Urban land: price indices, performance, and leading indicators. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 60(3), 396–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-019-09696-x.

[16] Arora, P. M. and Dastidar, A. G. (2022). Interlinkages between Credit and Housing Prices in Emerging Market Economies. Prajnan, 51(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0970844820220102.

[17] Albuquerque, B., Cerutti, E., Kido, Y., & Varghese, R. (2026). Not all Housing Cycles are Created Equal: Macroeconomic Consequences of Housing Booms. Journal of International Money and Finance,

161, 103496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2025.103496.

[18] Mueller, G. (2001) Predicting Long-Term Trends and Market Cycles in Commercial Real Estate. Working Paper 388. https://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/388.pdf

[19] Greenwald, D. L., & Guren, A. (2025). Do credit conditions move house prices? American Economic Review, 115(10), 3559–3596. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20211715.

[20] Rashad, A. (2025). Assessing Dubai’s housing market price cycles and bubble risk. Applied Economics Letters, 32(10), 1389–1393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2024.2304083

[21] Kaiser, R. (1997). The Long Cycle in Real Estate. Journal of Real Estate Research, 14(3), 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1997.12090911, p.250.