How effective is real estate as an inflation hedge? A perspective from the Gulf

GCC Inflation: perception and reality

At the beginning of 2023, the consensus perspective is that the global economy is far from out of the inflationary woods yet. After a global average of 8.8% last year, opinions now diverge as to the curve of the downward trajectory this year, from the IMF’s global estimate in October 2022 of 6.5%1, to a doveish projection of 3.1% for domestic inflation in December from the US Federal Reserve2 and S&P’s January forecast of 5%3. Markets have priced in US Federal Reserve interest rate hikes at least to mid-2023, with most analysts expecting that the inflationary environment will persist well into this year, with the most recent evidence from the European Central Bank citing inflation still in double figures, five times above target, albeit showing signs of eventually easing4. The Gulf region has scarcely been immune: amidst a generally positive recovery supported by advancing energy prices, GCC inflation came in at around 3.5% this year, with suggestions that it will ease to 2.6% in 2023 and stabilise around 2% in the medium term5, with Qatar experiencing the highest, Bahrain the lowest and Saudi Arabia’s data skewed by the VAT change during the pandemic. These levels had not been since 2018, although we should recognise that these are still lower levels than the average of the last decade, almost half the global average for 2022, and much lower than the MENA average, Egypt for example well into double figures, itself curbed as the World Bank noted by price controls and consumption subsidies6. In fact, as the Conference Board noted mid-year, they are amongst the lowest in the world, and are set to continue at comparatively lower rates in 2023.

The causes of inflation

Economists have traditionally disagreed over the causes of inflation,6 with monetarists pointing to the inability, or at least the unwillingness, of central banks to control domestic money supply. By contrast, Keynesians asserted that excess demand in the economy is largely responsible, pointing to the fact that historically, inflation has followed GDP increases with a lag, which meant that post-pandemic GDP gains were always likely to be a driver of inflation.7 In retrospect, global enthusiasm for a return to normality post-pandemic will be seen not to have been optimally managed, a narrative that has already begun.8 The Keynesian assertion is weakened by the comparison between the inflationary impact of the global financial crisis and the current impact of energy and other commodity price rises. Then, demand deficiency was met by ramping up government expenditures, which brought inflation in its wake. In the UAE, inflation peaked at 12.25% in 2008, a level verging on the point where established wisdom, at least, suggests that investment decision-making is at least compromised. Even more tellingly, to place the COVID-19 stimulus packages worldwide in context, they were two orders of magnitude greater than their equivalents in the global financial crisis.9

By comparison, the existence of cost-push inflation was always in principle accepted by both sides of the argument, but now it has taken centre-stage.10 In the Gulf, sectorally, transportation and food, beverage and tobacco have experienced the highest inflation rates, indications of post-pandemic recovery and commodity pressures respectively.11 The importance of identifying the cause of the current global inflationary tendency as at least partly cost-push is this: if supply bottlenecks caused by export restrictions – most obviously energy supplies but also food – is causing inflation, then they are only ‘transitory’ – as central banks described it12 – in the sense that their alleviation will be the necessary requirement for easing of price inflation.

Government response

Current government policies internationally compare very favourably with previous inflationary periods. World Bank President David Malpass noted recently, for example, that monetary policy frameworks are more credible—with clear price stability mandates for central banks in advanced and many developing economies alike.13

The room for manoeuvre for GCC governments is however comparatively limited. Their interest rate management policy cannot diverge too far from the US Fed – they have already succeeded in following US rate hikes most reluctantly without prejudicing the dollar peg, and in controlling domestic money supply. Similarly, they cannot take actions that will curb consumer prices without engaging in substantial subsidies, reducing their currency buffer stocks, risking stoking inflation themselves and – crucially – potentially prejudicing their fiscal stance. GCC governments are especially unwilling to recommence fiscal generosity given the crucial fact that Covid-19 expenditure has already weakened their balance sheets: they had been looking to recover now and over the next few years. There is some room for expenditures, whether by reducing VAT, controlling primary product prices, as for example the UAE has done, or releasing some strategic commodity reserve, but these are likely to be both selective and limited.This is economic weather that must be ridden out.

The impact on real estate

The famous monetarist Milton Friedman called inflation taxation without legislation, levied especially on those without the ability to hedge through real assets. In a perfect market, real assets should simply correlate with inflation, but historical evidence suggests strongly that real estate represents an effective inflation hedge, especially during periods of sustained high inflation.14 But this evidence at a high level of aggregation must be tempered by the realisation that sub-sectors perform differently, and that therefore the choice of real estate assets is crucial to the effective development of a hedging strategy. The hedge has not historically deployed immediately. Rather, real estate prices have typically adopted a U-curve in response to inflation. Immediate demand falls as residential purchasers in particular feel the bite of increased interest rates interacting with increased prices for their other expenditure items. Whilst the timescale of this response historically has been debated,15 this is evident globally this year: in the USA, for example, by April 2022 residential prices had fallen 5% to 10% yoy in some markets, with Europe now following the same trend. Historically, the percentage of index-linked leases has been an indicator of the effectiveness of commercial real estate as a short-term inflation hedge, especially where loans have been secured on a fixed-rate basis. As a result, positive commentary has surrounded the ability of relatively high-demand sub-sectors (prime residential, warehousing) at least partially to track inflation in the short term.16

Expert view

The evidence is strong that, in striking contrast to many other asset classes, returns from real estate have already proved to be an effective inflation hedge across the GCC. But not all real estate is equal in providing this protection, either by asset class or location. While inflationary hedge in residential real estate is a lot simpler to factor, inflation impact on commercial real estate reinforces the need for properly analysed rental projections, including the impact of inflation on industry and tenant-specific business risks, the differential effect of generalised inflation on cap rates between asset classes, and the impact on relative purchasing power and liquidity. On the part of investors, enthusiasm for real estate must be balanced in a higher interest rate environment with leverage levels, diversification and return objectives. That said, there is little evidence to suggest that rise in interest rates has so far led to any significant cap rate expansion for institutional grade deployments in the region.

But historically, both wage growth and high interest rates have been a corollary to high inflation, leading indirectly to rent growth and downward pressure on cap rates, whilst development investment also stumbles as a result of increased costs, further increasing the value of existing real estate. This does differ from the current global real estate market, already affected by strategic trends including work from home and the effect of on-line retail, which has curbed the ability to raise rents for retail tenants even in an inflationary environment, and both with flattened yield curves pointing to constraints on economic activity, and as yet, despite acknowledged labour shortages, sluggish global wage growth. Whilst a conservative perspective on the US market is understandable, given that only 7% of buyers are international,17 analysts are now also cautious about the prospects even for traditional real estate safe havens such as Switzerland.18

This conspicuously cautious global narrative makes a comparison with recent trajectory of real estate in the Gulf especially noteworthy.

The case of Dubai: residential prices and inflation

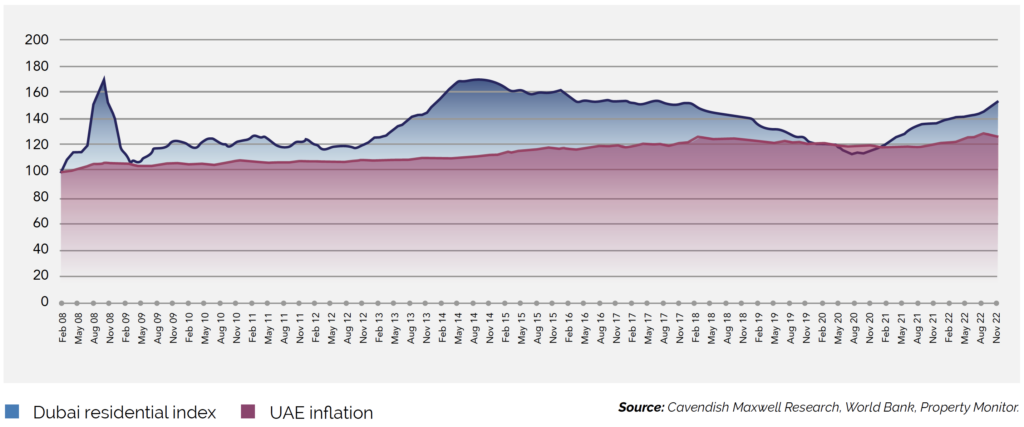

The evidence indicates that for almost all of the period since 2008, holding Dubai residential property has outperformed inflation. In this important practical sense, real estate has over-performed its role as an inflation hedge. Investors are scarcely likely to be worried that the actual correlation between real estate prices and inflation over this period is a relatively unexceptional 0.367, unless they were to draw the conclusion that in future, inflation might outpace residential property values – for which there is no evidence.

UAE inflation vs Dubai residential prices

The short-term response of the Dubai residential market does not accord with the established narrative, which is now playing out in other markets such as the US and Europe. The explanation is partly technical: housing is the largest component of the CPI across the GCC, ranging from a fifth in Qatar to a third in Kuwait. Other explanations include lower LTVs for residential owners, reducing the effect of interest rate hikes on affordability, and possibly even inverting it, as a result of Dubai’s strategic position in particular as a flight to quality for high net worth individuals.

Regionally, the robust short-term response both of residential and commercial markets can also be traced to the relative liquidity of Gulf banks by comparison to their Western peers.19 There may also be positive behavioural economic explanations of sectoral outperformance, given the generally high level of affluence and therefore arguably rational decision-making amongst Gulf investors.20 Longer term, this evidence is less surprising, as residential real estate worldwide has consistently outperformed general inflation. For example, in Canada, admittedly a country with a strongly performing residential market, from 2000 to 2020, overall inflation was 39% compared to 51.8% for new housing prices. Likewise for commercial property, the U-curve reverses longer-term, as once inflation expectations are normalised into business decision-making, real estate prices have historically staged a strong recovery. The correlation between demand-pull inflation and demand for commercial real estate – along with problems that inflation causes for development – has historically reinforced the sector’s ability to match and even pull ahead of general inflation. Commercial real estate as an inflation hedge has therefore been characterised as ‘strategically better over the long term: five, seven, or more years.’21

The case of Saudi Arabia: REITs and inflation

The case of the Dubai residential market also makes an interesting comparison with what has happened to REITs, for example in Saudi Arabia.

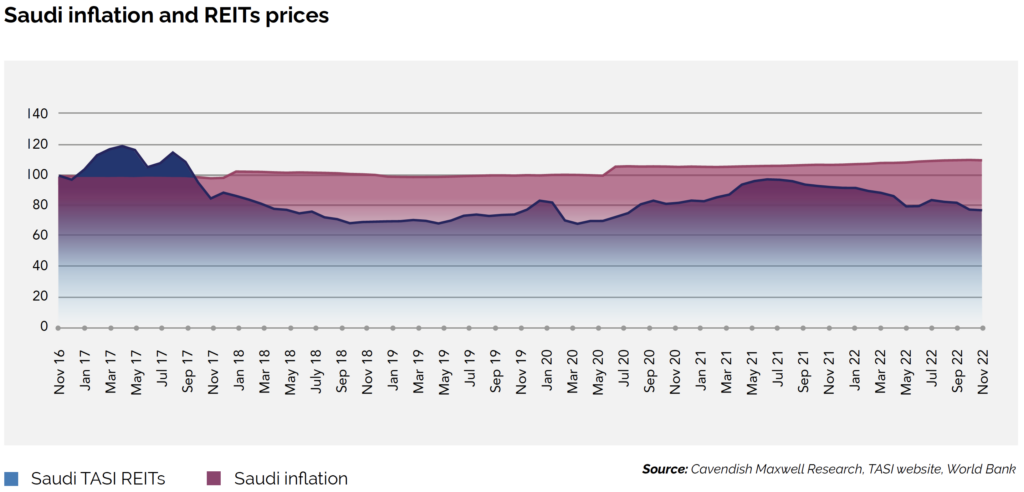

Saudi REIT correlation with inflation since 2016 is marginally higher, at 0.451, and the end result as of mid-2022 is at least a superior performance to overall inflation. But neither of these facts ought to encourage investors to regard the Saudi REIT market as better protection against inflation than the Dubai residential market: not only did Saudi REITs underperform by comparison to CPI for a prolonged period, but judging from the standpoint of mid-2022, they have provided less of an investment comfort zone in the event of future performance deterioration – which given on the whole greater leverage in REITs markets worldwide than in Gulf residential markets, is not entirely unexpected. It is consistent outperformance that interests investors – not correlation.

Saudi inflation and REITs prices

Longer-term this is consistent with international evidence. Asset-based investments have outperformed even gold and inflation-linked bonds22, consistent with the NAREIT study that showed dividend increases for US REITs outpacing inflation in 18 of the last 20 years; REITs tend to outperform in the high inflation periods, with ‘strong income returns offsetting falling REIT prices’23 (and vice versa). Likewise, if one were to include not only the capital value of REITs, but include rents as well (i.e. total returns), and compare with inflation generally as measured by CPI combined with some indicator of alternative cashflow, such as overall dividend payment ratios, the inflation protection they provide would be augmented.

This will naturally depend on the future trajectory of interest rates and their levels of leverage, but on average this would demonstrate significant inflation protection through REITs.

Critics respond that investors should also be concerned about asset volatility, which may be a necessary exchange for outperformance. But even traditional ‘riskadjusted’ performance indicators such as the Sharpe and Sortino ratios, which compare returns to volatility, point to the relative attractiveness of direct real estate in an inflationary environment24, though they achieve this by trading off liquidity, and even sacrificing diversification if only high-performing real estate assets are chosen.

Conclusion

The evidence overall is convincing that Gulf real estate represents a more than adequate defence against inflation, both short and long-term. Investors must recognise, however, that both for direct real estate and REITs, the granular choice of property will be crucial. As US evidence demonstrates, ‘the most resilient and best performing real estate is often the least glamorous – including housing, warehouses and self-storage’ – not as historically ‘core’ assets such as Grade A offices. For those investors already in the market, inflation provides good reasons to evaluate the inherent risks of their tenant portfolio, leverage levels and return objectives.

References

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022#:~:text=Global%20inflation%20is%20forecast%20to,to%204.1%20percent%20by%202024.

[2] https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20221214.pdf

[3] https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/top-10-economic-predictions-for-2023.html

[4] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.mp221215~f3461d7b6e.en.html

[5] https://www.icaew.com/technical/economy/economic-insight/economic-insight-middle-east

[6] https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/38065/English.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=

[7] See Jain, M. P., Sharma, A., & Kumar, M. (2022). Recapitulation of Demand-Pull Inflation & Cost-Push Inflation in An Economy. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 2980-2983

[8] e.g., Nersisyan, Y., & Wray, L. R. (2022). What’s Causing Accelerating Inflation: Pandemic or Policy Response? Levy Economics Institute, Working Papers Series, 1003.

[9] https://theconversation.com/as-inflation-looms-heres-how-real-estate-and-farmland-have-protected-investors-155854?gclid=CjwKCAjwtcCVBhA0EiwAT1fY72-SkvmF9niaehWg7kPffbwxWai_EBXMMLZdij_S_MFy_ooBgGm3LBoCpO4QAvD_BwE

[10] e.g, Taylor, L., & Barbosa-Filho, N. H. (2021). Inflation? It’s Import Prices and the Labor Share!. International Journal of Political Economy, 50(2), 116-142.

[11] https://www.conference-board.org/pdfdownload.cfm?masterProductID=38694

[12] https://www.ft.com/content/1c6a35d2-8a32-4563-93e0-07d63323e98e

[13] https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/supply-solution-stagflation

[14] https://bcf.princeton.edu/events/alexi-savov-itamar-drechsler-on-investing-in-a-high-inflation-environment/

[15] Sutton, G. D., Mihaljek, D., & Subelyte, A. (2017). Interest rates and house prices in the United States and around the world. BIS Working Paper No 665.

[16] https://argaamplus.s3.amazonaws.com/68112185-9470-4399-a3de-5a4b6e5368a7.pdf

[17] McGurk, Z. (2020). US real estate inflation prediction: Exchange rates and net foreign assets. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 75,53-66.

[18] https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/private-banking/docs/ch/privatkunden/eigenheim-finanzieren/credit-suisse-immobilienmonitor-q2-2022-en.pdf

[19] https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/220622-why-gcc-banking-systems-are-resilient-to-geopolitical-stress-scenarios-12403528

[20] See the insightful review here https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/BFI_WP_2022-41.pdf

[21] https://www.pbmares.com/inflation-impact-commercial-real-estate/

[22] https://www.troweprice.com/institutional/ac/en/insights/articles/2022/q2/asset-allocation-in-the-era-of-high-inflation.html

[23] https://www.reit.com/investing/investment-benefits-reits/reits-and-inflation-protection

[24] https://www.berkadia.com/a-better-way-to-assess-inflation-and-risk-in-real-estate/