Valuing luxury real estate in the Gulf

Understanding luxury

Luxury is a concept as old as philosophy itself. It has stirred debate for centuries. From the musings of Plato to modern economic thinkers like Werner Sombart and Thorstein Veblen, interpretations of the concept of luxury may differ, but they all seem to agree that luxury is an important aspect of society. Sombart championed luxury’s central role in capitalism[1], while Veblen gave us an entire theory of luxury goods.

However, defining the concept of luxury is not that simple because luxury is all about context. Analysts argue, rightfully, that we can’t take it out of its time and place[2]. Think about it – the modern ubiquity of mobile telecommunication, for example, would make a 19th-century aristocrat’s head spin! Even a “luxury” hotel from a century ago wouldn’t cut it for even the modest of travelers today.

What may have been considered luxurious in the past, may be a staple in the present. But even in the same time period, luxury can mean different things to different people and have varying degrees of importance in different societies. In the Gulf, for example, luxury consumption has been central to economic and social development in recent years.

Did you know that the study of luxury brands and goods has garnered so much international attention that there’s now an ‘Oxford Handbook of Luxury Business’?[3]

Luxury is also a hot topic for research these days. Academics as well as business leaders continue to dive deep into the world of luxury, exploring what makes us choose these goods, why we’re willing to pay extra for a luxury brand, and how it all ties into our generation, gender, and culture[4].

The enigma of luxury real estate

In the world of investments, where property reigns supreme as the largest global asset class, luxury and real estate took their time to form a partnership. The notion of ‘luxury property’ as an investment concept can be traced only as far back as the 1930s[5]. Ever since luxury property as an investment vehicle and its accompanying valuation challenges have kept economists intrigued.

A simple Google search reveals a considerable body of research on the subject up till 2019[6], and it’s likely that the research has increased significantly since then.

In the Gulf region, both ‘luxury’ and ‘property’ have been used as alluring marketing tactics in the past. While speculators may have been lured by the promise of ‘luxury,’ buyers have often found themselves with less than they bargained for[7] . However, the Gulf luxury market and the analytical tools to decipher it have evolved substantially in recent years. Branded residences have become integral to the luxury real estate scene, and eye-popping sales figures continuously underscore the concentration of wealth within these exclusive properties.

What’s truly noteworthy here is the gradual emergence of a unified global market, with the Gulf now occupying a prominent role. Banks in the Gulf are inundated with substantial loan applications against luxury properties, and like any astute financial institution, they seek solid valuation assurance. And that’s where the challenge lies.

Impact of negative exceptionalism on luxury real estate valuations in the Gulf

When it comes to valuing luxury real estate in the Gulf, two glaring pitfalls should be recognised and avoided without question.

First, is what we call ‘negative exceptionalism.’ At its core, negative exceptionalism is a bias—whether conscious or unconscious— that favours a select few traditional luxury real estate markets, like the well-trodden paths of New York, London, and a handful of European and OECD hotspots, including Sydney and Singapore. Unfortunately, this bias often comes at the expense of the newer Gulf luxury markets. The impact of negative exceptionalism on property valuations in the Gulf is two-fold. Firstly, values per square meter in established markets that barely raise an eyebrow become a matter of amazement when they emerge in the Gulf. Secondly, Gulf luxury markets are often perceived as having shallower pools of buyers, less available capital, and a lower willingness to pay, painting them as more fragile and inherently riskier.

However, the facts on the ground tell a different story altogether. From a demand perspective, consider Norwegians investing in Dubai, for instance. Their probability of owning Dubai real estate rises with their wealth, and this trend holds true all the way up to the top 0.01% of the wealth distribution[8].

On the supply side, concerns about transparency are not exclusive to Gulf markets. The US Department of the Treasury, for example, has highlighted the risk of anonymous companies using real estate transactions to acquire valuable assets in the USA itself[9] .

This dichotomy in the perceptions of Gulf markets versus Western markets is not new. We’ve encountered similar bias in the past, be it in the realms of macroeconomics, automobile manufacturing, international services, and various other sectors.

The second valuation pitfall is closely related to the first. Investors tend to assume that because the Gulf real estate market is inherently different than other established markets, it’s impossible to find comparables for properties in Gulf luxury real estate. This assumption, in turn, supposedly leads to less reliable valuations.

Two decades ago, negative exceptionalism might have made sense and even seemed reasonable. A decade ago, it could have been somewhat understandable, although its rational foundation was already dubious. Today, however, it’s neither understandable nor reasonable. It may still be explainable, though, considering the relative lack of information and discussion surrounding luxury real estate in the Gulf, whether in academic publications, gray literature, or even, quite surprisingly, on social media platforms.

Is there a global luxury real estate market?

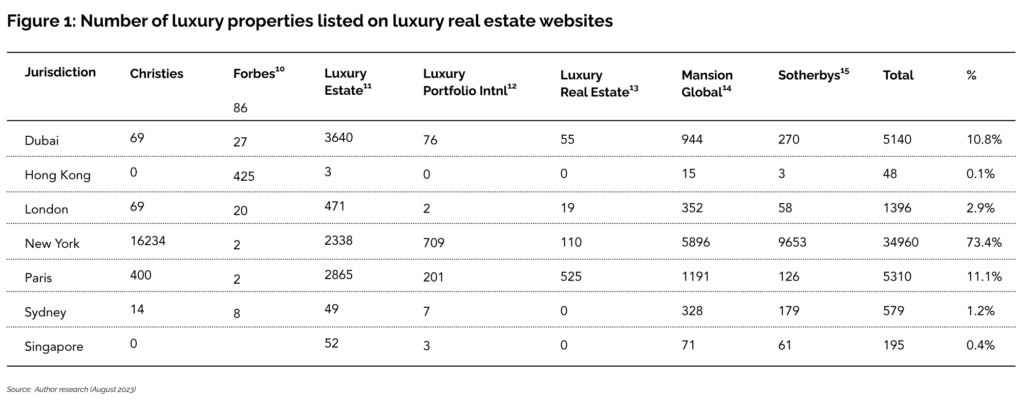

Evidence of a global luxury real estate market exists, although it often doesn’t receive the recognition it deserves. One piece of this puzzle is online marketplaces that cater to luxury real estate on an international scale. It’s important to note that these platforms may not always provide a perfectly reliable guide to pricing, especially when compared to their national counterparts that cover the broader real estate market. Plus, we’ve noted that many truly luxury properties often don’t even make it to the open market, whereas the prices of the ones that are listed vary significantly from platform to platform. And in any case, the number of bidders involved in the sale of luxury properties is minuscule.

Therefore, it is advisable to approach online data with a degree of caution. Instead of viewing online data as a source of precise average pricing, it should be utilized to extract valuable insights into how the market is evolving.

Truth is luxury real estate is a complex market. In fact, Forbes has now identified sixteen distinct subcategories within the realm of luxury real estate. The unique factors of climate, culture, and development patterns in the Gulf region mean that it doesn’t directly compete in all these subcategories. Nevertheless, Dubai has risen to be regarded on par with, and often above, traditional Western capitals as a preferred luxury real estate destination. It’s clear that the argument for negative exceptionalism no longer holds water.

Two quantitative measures of luxury real estate

When it comes to valuing luxury real estate, quantitative measures are indispensable. However, it’s important to make a significant distinction right from the start—between absolute and relative prices. For example, Forbes reported that globally “On average, sales prices of luxury residences in 2022 were 34% higher than in 2017[16].” But what does this really signify?

There are two fundamental ways to conceptualize luxury real estate, which we can distinguish as the absolute and the relative approaches. The absolute approach sets a minimum value for luxury real estate at a given time, whether in absolute price or price per square meter. This minimum varies by location, taking into account factors such as jurisdiction and proximity to city centres or concentrations of luxury real estate. However, there are two notable issues with the absolute approach. Firstly, there is no international or even jurisdiction-specific consensus on what these minimum values should be. Luxury values differ significantly on the global stage. For instance, both Christies[17] and Luxury Portfolio International[18],[19] defined luxury housing as starting at over US$1 million—a figure that may seem surprisingly low to those accustomed to observing multi-million-dollar villas frequently changing hands in Dubai, for example.

Secondly, absolute prices fall short in distinguishing quality from quantity. For instance, a vast sheep farm in Australia might command a high price, but it lacks luxury in any meaningful sense. Conversely, a luxury apartment in Dubai might fetch a substantial premium compared to the market average, driven by factors such as location, finish, branding, and other considerations.

The relative approach, rooted in the local context, proposes that luxury real estate is defined by a certain percentage of any given market—rather than simply being tied to the market’s average. It’s important to note that relative definitions can shift depending on sales volumes within different market segments. However, as of yet, there is no consensus on which specific percentile should be used. Zhann Jochinke, Director of Market Intelligence and Research at Cavendish Maxwell and an advocate of the relative approach suggests that two easily comprehensible percentiles are the top decile and top percentile of any market. The historical trends for these percentiles in Dubai and the relationship between them both indicate a rapidly maturing market in the early part of the last decade, with the most significant luxury properties now primarily found in apartments. This is explained by the considerable disparities in their location, quality, and other determinants of price in Dubai.

Figure 2: Comparative sales prices in Dubai

Figure 2: Comparative sales prices in Dubai

Figure 2 tells a compelling narrative, offering a window into Dubai’s evolving luxury real estate landscape. It paints a clear picture of how the relationship between the least and most expensive ten percent of properties has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past decade. As Dubai’s real estate market has matured, the chasm that once existed between these two extremes has dramatically narrowed. What was once an astonishing difference of nearly twelve times has now settled into a much tighter range, fluctuating between two and six times more expensive.

Notably, the past dynamic, where villas enjoyed the widest price disparity, has shifted. Today, it’s luxury apartments that have taken centre stage, a testament to the rise of opulent apartments that can compete both in terms of luxury and price on a global scale. This transformation underscores the changing dynamics of Dubai’s real estate landscape. A similar pattern emerges when we examine an even more refined comparison—between the highest and lowest one percent of Dubai’s residential properties. While the price gap naturally widens in this context, it follows a comparable trajectory, highlighting the market’s noteworthy evolution.

Innovating new approaches to valuing luxury real estate in the Gulf

At Cavendish Maxwell, we are at the forefront of developing more robust tools for reliable valuations, focusing on market value, rent, and replacement value to meet the expectations of both lenders and investors alike. These valuation bases and methodologies are standard practice in mature markets and often mandated by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS).

One of the fundamental valuation techniques, particularly for luxury properties, has always been the use of comparables. This involves assessing sales prices and, to a more limited extent, property listings. Investment yield valuation, which capitalizes on market rents, provides an invaluable and well-established alternative methodology. It serves as a useful cross-reference to validate valuations based on comparables. In essence, our valuation of luxury real estate follows established procedures in these respects.

However, where innovation truly shines is in the implementation of these methodologies. In some cases, especially within the top decile (though not necessarily the top percentile), property valuers can draw on data from exclusive sources such as Property Monitor by Cavendish Maxwell as well as from internal transaction records. This rich data provides them with recent local sales prices and rental comparables, giving them the confidence to restrict comparables analysis to specific localities. In other cases, especially concerning major new branded developments, there are three key modifications to the methodology that are rapidly gaining international recognition.

The first modification involves embracing broader comparisons, occasionally incorporating international evidence. While this isn’t entirely novel, especially in broader business valuations, there are nuances to consider. From the RICS standpoint, there are no barriers to using international evidence, for example, in calculations related to the cost of capital[20] or the valuation of international brands. However, the incorporation of international evidence into real estate valuations is a blend of science and art.

Even the requirement that comparables should align with the markets the target company engages in[21] can be a complex task. For real estate, the RICS rightfully emphasizes that comparables must be ranked based on relevance and significance[22], with considerations for the accuracy of reported market values.

How much property can you purchase around the world with $1 million?

3 challenges of Valuation by comparables

When making comparables-based valuations within the global real estate market, several critical considerations come into play.

First and foremost is the issue of country risk. For instance, according to Fitch, the USA’s credit rating stands at AA+[23], while the UAE is rapidly approaching AA-[24]. However, sovereign risk merely scratches the surface. There are sub-sovereign risks with intricate relationships to their sovereign parent[25] and risks that extend to the municipal level, as the stories of New York’s financial struggles and Detroit’s bankruptcy have shown[26]. From the perspective of international investors, these risks, including potential currency implications, are likely factored into local real estate values. Therefore, adjustments are essential for a valid comparative analysis. For instance, from a UAE and Saudi standpoint, the currency peg with the US dollar and the resulting close correlation of interest rates and market conditions lend credence to the use of US comparables.

Secondly, at a more detailed level, valuation has evolved to incorporate a wider array of considerations. Facilities matter significantly. Buyers now prioritize outdoor spaces and access to lifestyle amenities, often seeking to replicate their vacation experiences in their daily lives[27]. To address these evolving demands, databases have emerged that encompass multidimensional aspects of luxury properties. These databases factor in details such as proximity and ease of access to beaches and leisure resorts, the precise nature of sea views, and the time required to reach key destinations, including airports.

These tools have become integral to luxury real estate valuation. However, it’s crucial to note that this information is typically proprietary and, despite some convergence, still depends to some extent on jurisdiction and even city. This is due to unavoidable climate differences and cultural factors that influence preferences.

Thirdly, in the realm of branded developments and residences, the relative importance of specific brands and their interconnectedness with services and build quality plays a pivotal role in luxury valuation practices. To accurately assess the significance of branding at the level of individual development, a comprehensive approach is required. This entails closely observing the actual preferences of High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) for the top decile and Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (UHNWIs) for the top percentile. It also involves continuous engagement with developers and investors and a brand valuation perspective that encompasses luxury as a multi-layered concept. This includes developers, design, architecture, co-branding, and a perspective that extends beyond the confines of real estate to the overall value of luxury brands on a global scale.

Conclusion

Reflecting on the rapid evolution of luxury real estate valuation, it’s tempting to assume we’ve reached the peak of knowledge and valuation understanding. However, history reminds us to maintain a longer-term perspective. Luxury real estate’s global journey is likely still in its early stages.

While established methodologies will remain vital for decades, they are continually enhanced. Organizations like Cavendish Maxwell are developing multi-dimensional databases to expand data and refine valuation techniques.

So, is valuing Gulf luxury real estate more challenging than other categories? Not necessarily, but it demands specialized skills and access to databases for reliable valuations. As luxury real estate continues its journey, these skills and resources will remain indispensable.

[1] Sombart, W. (1913) 1967. Luxury and Capitalism. Translated by W. R. Dittmar. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

[2] Kasztalska, A. M. (2017). The economic theory of luxury goods. International Marketing and Management of Innovations: International Scientific E-Journal, 2, 77-87.

[3] Donzé, P. Y., Pouillard, V., & Roberts, J. (Eds.). (2022). The Oxford handbook of luxury business. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[4] e.g. John, A., Pujari, V., & Majumdar, S. (2023). Impact of social media marketing on purchasing intentions of luxury brands: the case of millennial consumers in the UAE. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 14(3), 275-293.

[5] Wehrwein, G.S. and Spilman, R.F. (1933) Development and Taxation of Private Recreational Land. Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, 9(4), 340-351.

[6] Google’s explanation is that website dating has become less reliable

[7] Cooper, P. (2010) ‘Luxury Property is the best buy’. The National, 19 February. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/luxury-property-is-the-best-buy-1.550147. [Accessed 25 August 2023].

[8] Alstadsæter, A, Planterose, B., Zucman, G. and Økland, A. (2022). Who owns offshore real estate? Evidence from Dubai. EU Tax Observatory Working Paper No 1. Available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/events/2022/june/workshop-hf-and-alstadsaeter-paper-2.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2023], p.3.

[9] Bieler, S. A. (2022). Peeking into the House of Cards: Money Laundering, Luxury Real Estate, and the Necessity of Data Verification for the Corporate Transparency Act’s Beneficial Ownership Registry. Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L., 27, 193, p.222.

[10] https://www.forbesglobalproperties.com/

[11] https://www.luxuryestate.com/

[12] https://www.luxuryportfolio.com/

[13] https://www.luxuryrealestate.com/

[14] https://www.mansionglobal.com/

[15] http://sotherbysrealty.com/

[16] Forbes Magazine (2023) Perspectives: An outlook on global luxury real estate. Available at: https://media.forbesglobalproperties.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Perspectives-by-Forbes-Global-Properties-Annual-Report-2023.pdf [Accessed 19 July 2023].

[17] Christies (2018) Luxury Defined. An insight into the luxury residential market. Available at: https://luxurydefined.christiesrealestate.com/hubfs/CIRE%20White%20Paper%202018.pdf [Accessed 19 July 2023].

[18] Luxury Property International (2022) State of the Market for Luxury Real Estate (SOLRE) 2022. Available at: https://ml.globenewswire.com/Resource/Download/3c08ae81-d703-4faf-8ea2-dc5c9c70ed7e [Accessed 20 July 2023].

[19] Luxury Property International (2023) State of the Market for Luxury Real Estate (SOLRE) 2023. Available at: https://www.leadingre.com/downloads/LP/SOLRE%202023_GENERIC.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2023].

[20] Indian Institute of Management (2021) Study on the Determinants of Cost of Capital of

Cochin International Airport Limited (CIAL). Available at: https://www.aera.gov.in/uploads/stack_holder/16466399164567.pdf [Accessed 27 August 2023].

[21] Fazzini, M. (2018) Business Valuation: Theory and Practice. Cham, Springer, p.29.

[22] RICS (2019) Comparable evidence in real estate valuation. 1st Edition. London, RICS. Available at: https://www.rics.org/profession-standards/rics-standards-and-guidance/sector-standards/valuation-standards/comparable-evidence-in-real-estate-valuation [Accessed 20 July 2020].

[23] Fitch (2023) Fitch Downgrades the United States’ Long-Term Ratings to ‘AA+’ from ‘AAA’; Outlook Stable. 1 August. Available at: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-downgrades-united-states-long-term-ratings-to-aa-from-aaa-outlook-stable-01-08-2023 [Accessed 27 August 2023].

[24] Fitch (2023) Fitch Affirms the United Arab Emirates at ‘AA-‘; Outlook Stable. 13 July. Available at: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-affirms-united-arab-emirates-at-aa-outlook-stable-13-07-2023 [Accessed 27 August 2023].

[25] Mohapatra, S., Nose, M., & Ratha, D. (2016). Impacts of sovereign rating on sub-sovereign bond ratings in emerging and developing economies. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7618. Washington DC, World Bank. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2756812. [Accessed 27 August 2023].

[26] Davidson, M. (2020). From Big to Small Cities: A Qualitative Analysis of the Causes and Outcomes of Post–Recession Municipal Bankruptcies. City & Community, 19(1), 132–152. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/cico.12449 [Accessed 27 August 2023].

[27] https://media.forbesglobalproperties.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Perspectives-by-Forbes-Global-Properties-Annual-Report-2023.pdf