Yields and Recovery: Four major questions

What determines yields?

Real estate yields are usually defined as net income receivable over transaction price paid. Both terms are subject to varying definitions, whilst yields themselves apply to initial investments on exit or over a given lifetime. A standard yield model uses three independent variables: the risk-free rate, the expected rent, and the risk premium[1], all of which assume standardisation of tenant, location and building quality.

It is little surprise that local rental growth paths, interest rates and inflation are all held out to be significant determining factors for yields. Recent research has applied different techniques, but to the same variables and with similar results[2]. In all cases, expectations of the future trajectory of these variables can be expected to be as influential, if not more so, then their current or historical values—but much more difficult to identify and track. Information is asymmetrically distributed between market actors and even strategic objectives differ. As a result, market yields can never be completely explained.

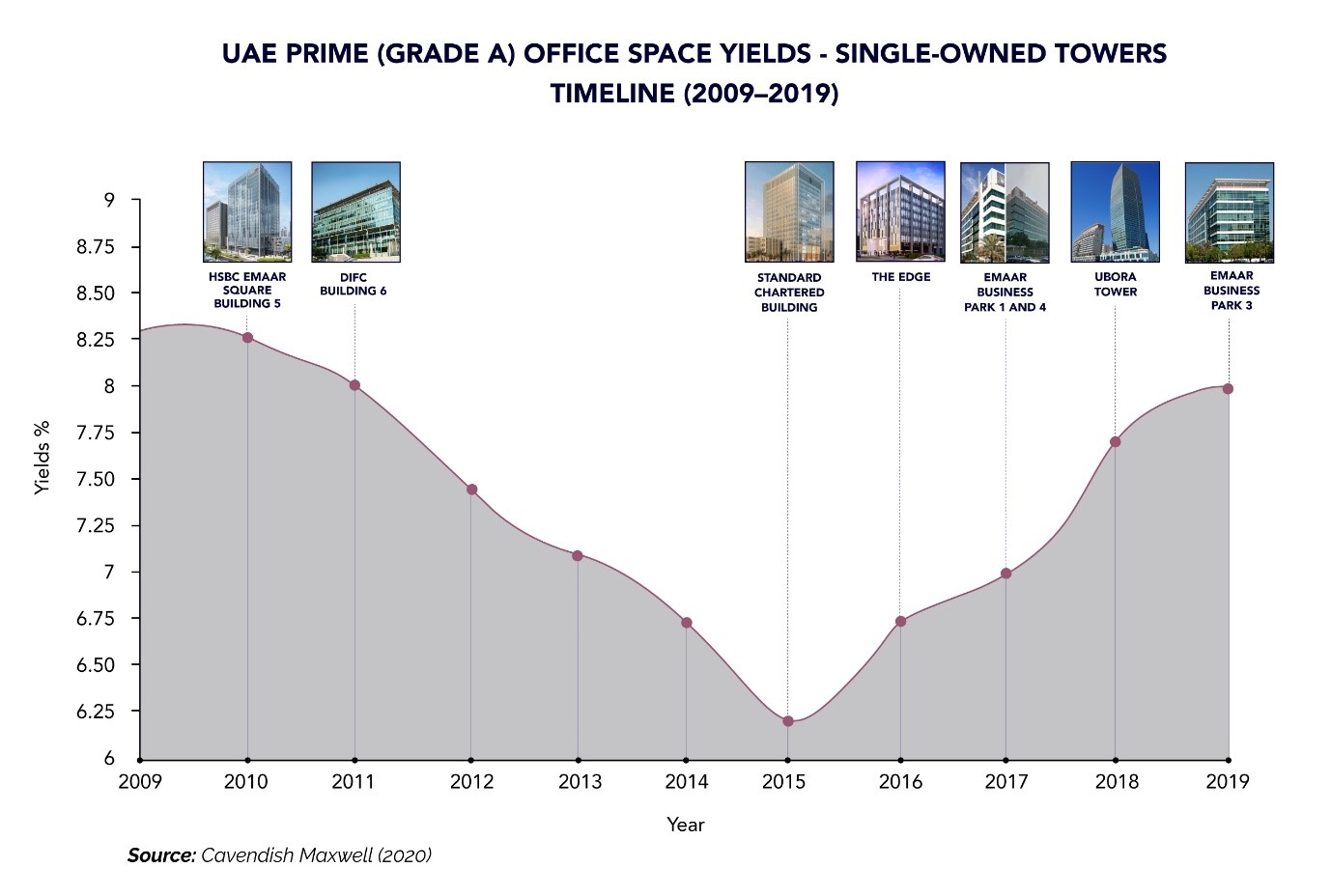

What we do know for sure, however, is that as these determining factors oscillate, yields themselves are scarcely stagnant: classic real estate cycles of between four to ten years, long economic cycles and links to the capital markets have all been observed, with varying leads and lags, and dependencies on the level of construction in the market. For Grade A offices, shown in the chart below, the yield profile has moved gradually from an historic low of 6.25% (albeit this was a single let) in the market peak in 2015, back out towards 8.25% in 2019, similar to levels seen in 2010.

The chart shows another important point: as the UAE real estate market has acquired more of the characteristics of a developed market, the pace of the cycle itself has slowed. Why might this be?

There may be several reasons. For example, in developed markets, tenants seek to move from lower to higher grade buildings during an economic downturn, resulting in volatility. In the Gulf, however, the relative homogeneity of high-quality constructed buildings, all built in a relatively compressed timescale, militates against this. More importantly, liquidity in Gulf markets is much greater on the upswing than when markets decline, with less urgent need for capital and therefore fewer distressed sales. The advantages of relatively low gearing and government-backed enterprises can be clearly discerned. It follows from this that residential markets are likely to be more disparate in terms of yields[3], which is what Property Monitor’s database has indeed shown for Dubai.

What happens to yields in Gulf real estate markets significantly depends on the answers to four key questions.

What will happen to interest rates?

The risk-free rate is a key determinant of real estate yields, as has been consistently suggested, albeit that the property cycle responds only with delays to current macroeconomic indicators such as changes in interest rates, flows of funds, and incomes[4]. So a rapid rise in US interest rates would eventually be matched by a rise in real estate yields in the Gulf, given the USD peg and the close correlation of local with US interest rates. What is the risk?

Conventional wisdom does suggest that the result of the current crisis will be a reduction in US creditworthiness, and a rise in US Federal Reserve rates. But as the Brookings Institute has noted, whilst in principle there is only so much the government can borrow without raising interest rates and crowding out private investment, interest rates are at historic lows and ‘there is a lot of room to increase borrowing without having to worry too much right now about impairing private investment’[5]. That is without assuming any more radical measures on the part of the Federal Reserve. In addition, public policy measures taken this year have been ‘very effective at containing the rise of borrowing costs for firms’[6]. Problems may be stacking up for future policy to deal with, but higher interest rates as we emerge from the crisis seems very unlikely to be amongst them.

Should the UAE still be seen as an emerging market?

This question threatens to slay two long-lived shibboleths. Globally, this crisis stands a chance of being characterised as the first when the traditional distinction between the yield response of developed and emerging real estate markets inverts, since volatility in developed markets is likely to be greater. This depends simply on how effectively developing countries continue their relatively superior responses to Covid-19.

Secondly, total returns in real estate have traditionally been driven primarily by income returns, which have been relatively predictable. Capital gains are a much smaller component of total returns, and they have been regarded as more volatile. This crisis may also alter the balance of risk between the two components of total return.

Whether or not volatility turns out be higher in developed or developing countries, can UAE yields continue to remain significantly higher than those in competitor markets? Shorter lease lengths are only a partial justification. Analysts have expected yields to fall for over a decade, and the chart above no doubt reflects an emerging reality. However, if yields in areas of good quality infrastructure are generally relatively higher[7], so long as sentiment continues to demand just shy of double digits around the region, there is little reason to presume that observed trends will alter as the crisis passes.

What shape will the recovery take?

Analysis of six Asian office markets between 2007 and 2015 indicated that increasing excess liquidity (using Gross Domestic Product growth as a proxy) tends to reduce office yields as investors lifted value without lease renewals and rents keeping pace[8]. Conversely therefore, the rapidly declining liquidity currently observable throughout Gulf real estate markets ought to raise yields. Why might this theoretical conclusion not hold?

The reason may lie in the difference in structure between Western and Asian real estate markets and the Gulf. Whilst macro-economic factors may still sway investor sentiment, observed needs for additional return in the medium term amongst Gulf investors are significantly lower, reducing excess liquidity pressure when markets move rapidly upwards, but equally curbing pressure to sell when they turn down. Whatever shape the market recovery takes, the effect on yields overall in markets such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia can be expected to be attenuated in international comparison.

How will different sectors respond?

Deals may have been placed on hold but yield changes do not yet seem to be part of any potential renegotiations (at least for now anyway). This is perhaps also because the Gulf had already experienced three to four years of consecutive price declines and was already showing good value pre Covid-19.

Demand for single let logistics around the 8.5%-9.5% yield mark and neighbourhood retail around 8-9% has remained significant even during the crisis. Although some land in private ownership may well exhibit greater volatility and hence, rising yields in transactions driven by foreclosures, what is striking about the UAE commercial property landscape is the extent of yield homogeneity between different sectors, both in terms of actual percentages and rates of change. There may be many causes for this, which is certainly not how commercial property markets have traditionally behaved in developed markets. One possibility is that redevelopment opportunities are already priced into sales; another is that despite plenty of evidence, investors do not yet perceive risks as varying so substantially between sectors as they might be encouraged by their advisors to do. What seems certain is that the relative yield disparity between sectors will remain tighter in Gulf markets than in other developed markets.

Conclusion

As the UAE market in particular has developed, with other Gulf markets not far behind, both yields themselves and yield volatility have declined in tandem. The combination of ownership and debt structures with stable interest rates provides most of the explanation for a very different outcome to that observed in other markets that have made the same transition.

Traditional real estate cycles based on high levels of indebtedness and clear divisions between the public and private sector are not necessarily applicable in the Gulf. This will not change in the short or even the medium term. So, unless the recovery results in a radical elevation of interest rates, evidence suggests that a radical rise in yields overall is unlikely. If investors want to benefit from higher yields, they will have to heighten their due diligence, review localities that they had perhaps previously ruled out, and even contemplate redevelopment opportunities.

[1] Henig, S., Tsolacos, S. and Nanda, A. (2016). Which sentiment indicators matter? An analysis of the European commercial real estate market. Henley Business School Discussion Paper ICM-2016-04. Available at: https://assets.henley.ac.uk/legacyUploads/pdf/research/papers-publications/ICM-2016-04_Heinig_et_al.pdf?mtime=20170410170908 Retrieved 30 April 2020.

[2] e.g. Szweizer, M. (2019) A new model for Auckland commercial property yields. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 37(1).42-57.

[3] Reed, R. and Wu, H. (2010) Understanding property cycles in a residential market, Property Management 28(1), 33-46.

[4] Pugh, C. and Dehesh, A. (2001) Theory and explanation in international property cycles since 1980. Property Management 19(4), 265-297.

[5] Sheiner, L. and Wessel, D. (2020) Where is the US government getting all the money it’s spending in the coronavirus crisis? Brookings Institute March 25 2020. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/03/25/where-is-the-u-s-government-getting-all-the-money-its-spending-in-the-coronavirus-crisis/ Retrieved 30 April 2020.

[6] Faria-e-Castro, M.,Kozlowski, J. and Ebsim, M. (2020) Corporate Bond Spreads and the Pandemic. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis April 9 2020. Available at: https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/april/effects-covid-19-monetary-policy-response-corporate-bond-market Retrieved 30 April 2020.

[7] Yieldfinda (2020) Major Factors affecting the yield of a commercial property. Available at: https://www.yieldfinda.com/commercial-real-estate/major-factors-affecting-the-yield-of-commercial-property/ Retrieved 30 April 2020.

[8] Kim, K-M., Kim, G. and Tsolacos, S. (2018). How does liquidity in the financial market affect the real estate market yields? Journal of Property Investment & Finance 37(1), 2-19.