Branded Residences: Four Key Considerations

Introduction

The significance of brands and branding for the consumer goods industry is beyond the slightest doubt. The combination of generational effects and online marketing has served to reinforce their importance during the last two decades. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the Gulf, where branded luxury goods, in particular, have formed a larger percentage of consumer spending than anywhere else.

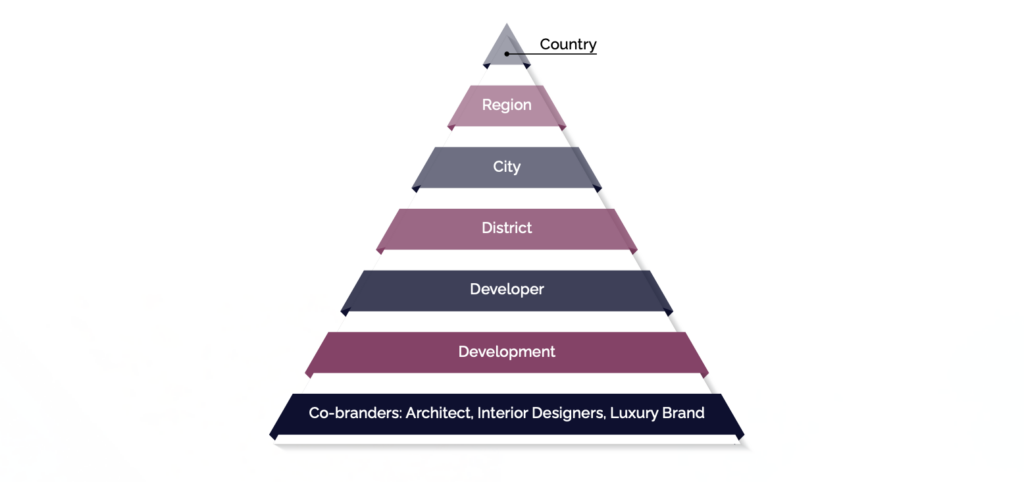

Branding across the different sectors of the real estate industry worldwide has, however, lagged Introduction behind fast-moving consumer goods, automobiles, and electronics. There are several reasons for this. Real estate development has traditionally been an industry with very low levels of concentration, virtually a cottage industry in some jurisdictions. Developers have not been able to invest financially in brand creation, seeking instead to grow their own brands through conventional marketing. The development process itself has also not helped: the development branding task has been complicated by the need to brand at multiple layers, many of which lie beyond the control of individual developers.

Figure 1: The branding pyramid in real estate development

Co-branding can range from the use of a single white goods supplier through to celebrity architecture and the association of a consumer goods brand with a development. Nowhere has this been better exemplified than in the rise of high-end developments that are characterised as branded residences, which now stand as an important real estate asset sub-class. In the Gulf such developments are now particularly important, including a growing part of luxury real estate in Saudi Arabia. There are however important issues for investors and occupiers to consider.

1. Defining branded residences

The idea dates back a century, when the SherryNetherland hotel on New York’s Fifth Avenue sold 165 apartments. The Four Seasons Boston in 1985 has been cited as the reemergence of the concept in more recent times. Now, the emerging branded residences sector is the fastest-growing segment of real estate branding globally.[1] Intuitively, what is involved is the choice of a foreground co-branding strategy by the developer as opposed to primary reliance on their own brand. Reflecting the diversity, Property Monitor has carefully chosen a wide definition:

“Branded residences are residential properties where there is public disclosure of an agreement between the developer and one or more non-real estate related organisations to manage, licence, provide services or be otherwise closely associated with the development”

This definition avoids multiple pitfalls. It does not assume that the partner organisation is necessarily a luxury goods brand. Cavendish Maxwell has already started analysis under four separate headings: hospitality, fashion, entertainment and celebrities, and jewellery. These sectors are well-established in the city. For the time being, hospitality brands dominate, but this may change in future. For example, there have already been successful co-brands between developers and automobile brands such as Bugatti, Bentley and Mercedes, as well as with Disney[2], Cipriani[3] and many others. It is certainly possible, even likely, that further sectors such as IT and cruise lines, aviation and entertainment will become involved. The latter two on this list also strongly suggest that what started as a purely luxury phenomenon is now percolating through the entire real estate market. There have also been examples of non-real estate organisations creating their own developer to which they can then attach their branding. John Lewis in London is an example.[4]

The above definition also does not assume that all branded residences will necessarily be high-end luxury property. And nor does it assume that the residences will necessarily be sold rather than leased out. Citra Living by Lloyds Bank in the UK is an example of ‘build-to-let’.[5] Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the definition does not assume that branded residences will always be in high demand or necessarily achieve higher valuations than non-branded properties. Indeed, there are examples worldwide where this has not happened. For now, however, and especially in the Gulf, developers are focusing on luxury branded residences for sale.

2. Brand valuation and valuing branded residences

Historically, there have been three methods by which brands themselves have been valued and these methods closely mirror the approach used in real estate valuation. Income-based methods have focused on capitalising on sales price premia or – arguably more importantly for the brand owner – excess earnings. The value of a national brand specific to real estate might be estimated through a methodology of surveying potential purchasers, starting with a generic apartment without an identifying location and then introducing locations and asking participants whether they would pay more (or less) for it.

By comparison, market-based methods have focused on the value achieved by the sale of brands themselves, although instances where such sales have not been accompanied by actual production are rare. Finally, cost-based methods rely on estimates of either the value expended in reaching the brand’s current state or the replacement cost to build it again. Various combinations and proprietary methods of brand valuation exist from consultants such as Brand Finance,[6] Kantar BrandZ,[7] and Interbrand.[8]

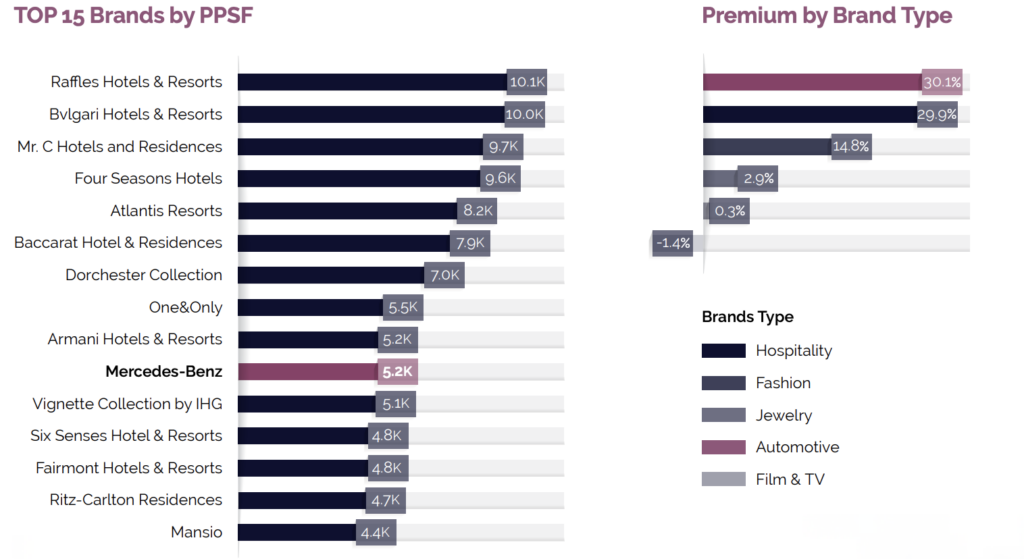

Compare this to the valuation of branded residences themselves. For several years, what has been available has only been a generic price premium between branded and non-branded, whether expressed globally or in some cases at the national level. This initial approach is now being rapidly superseded by a two-fold approach, employing databases with a high level of individual property data such as Property Monitor.

First are raw price data by development which reveal which branded residences achieve comparatively high sales prices (and rentals) in specific geographical areas. At a high level of aggregation this can be across all of Dubai, for example. At a much more granular level this can compare sales prices for specific developments which feature individual branded towers. This approach allows for flexibility: individual users can decide themselves whether particular developments are branded or not. Its disadvantage is the lack of focus on the agreement between the developer and a defined other party and therefore the extent to which the development relies on joint marketing for its valuation.

Second are price and rental premia, comparing branded with non-branded developments. This second approach can vary in complexity from straight averages to the use of complex regression models that seek to eliminate differences such as apartment size, location and aspects of build quality – elements that drive value and may be correlated with branding but are not identical to it. It is worth noting that, as yet, both price and rental premia apply only to new construction, as reliable evidence at a high level of detail from several years at least is required to determine long-term brand valuation premia satisfactorily in the resale market. Analysis based on comparing the sales prices of specific properties, known as repeat sales analysis, is now possible using comprehensive and detailed databases such as Property Monitor.

The task is still not easy: simply comparing the sales price in 2024 of a branded residence built in 2021 to one built in 2023 without making a series of adjustments for annual price increases makes little sense. Private equity has the same problem, which it resolves through the concept of ‘cohorts’, one for each year. Reporting on annual cohorts does not entirely solve the data problem, however, as annual cohorts of branded residences will have different geographical and qualitative compositions.

Both approaches are illustrated by Cavendish Maxwell’s recent presentation at the Future Hospitality Summit, which represents the beginning of the new era of detailed, regular reporting on both counts, relying on databases of thousands of sales points, required by developers and investors alike.[9]

Figure 2: Valuation of branded residences: insights from Dubai

From a developer perspective, this provides input to forecast sales prices and schedules as well as rents and lease-up periods, enabling a comparison to be drawn between the branded and non-branded projections. But this represents only one side of the coin. The other is the structure and cost of the agreement for the developer. As information on sales and rents proliferate, data-intensive consultancy can provide insights into how much value different aspects of the offering from the branding partner will contribute, and which elements represent payments by the developer for products or services that do not directly add value. Combining demand and supply analysis enables a cashflow valuation approach which compares the marginal benefits with the costs. An investor will similarly compare the additional cost per square metre of the branded residence with their projected increased rents and sales price in order to determine the scale of their net benefits.

3. Geography and market expansion

Developers, investors and valuers now have their task complicated by the intense competition at both the national and city level, a trend that is only expected to intensify. In the Gulf, Dubai is no longer alone; other cities have now begun to create branded real estate. Two examples, among many, from the Gulf are Riyadh, where the Elie Saab[10] and Ritz-Carlton[11] brands have now joined what is becoming a growing market;[12] and Muscat, which also has its own branded residences, notably the Mandarin Oriental.[13] It is likely that virtually every major city in the Gulf will have its own branded residences market. Further afield countries as diverse as India[14] and the Philippines[15] are also seeing strong growth in the sector.

But there is a further dimension. These markets are already competing with one another. Even more, as the international luxury market as a whole coalesces into one single global market, branded residences are set to follow. That’s a bold claim, but it is supported by two key pieces of evidence.

First, buyers are increasingly international. Brokers suggest that more than 200 nationalities are buying real estate in Dubai.[16] Because of the lack of uniform definitions, there is no accurate comparable data for branded residences. However, every report highlights that the market includes a diverse mix of buyers, with UK, Indian and local buyers consistently mentioned. Brokers are collaborating internationally and presenting a diversified range of options across jurisdictions to their clients.

Second, prices and rents for comparable branded residences are increasingly being presented internationally by chartered surveyors that have access to relevant property data. Apartments in Miami are providing benchmarks for costing analysis in Dubai; serviced apartments in London are serving the same purpose for Riyadh. Exchange rates will always pose a problem but, thanks to the dollar peg, this is less so in the GCC than in other jurisdictions.[17] Moreover, the evidence suggests that buyers are prepared to accept the risk at the individual property level as their portfolios are already internationally diversified and managed for currency risk, often using traditional risk management instruments.[18]

4. Attributes and lifestyle

Equally important for decision-making and valuation are the attributes of individual branded residences, which are now common international marketing currency. One of the most well-known and idiosyncratic is the ‘Dezervator’ car elevator facility provided at the Porsche Tower in Miami.[19] Attributes that have been more familiar for several decades include access to hotel-style or actual hotel services such as laundry, spas, health and other clubs, valet, concierge, security swimming pools and room service, as well as more specialised services such as carefully tailored personalisation, social interaction, transport and pet care. [20] Developers are now engaged in actively searching for new services to offer, whether private beaches – as Armani has done at Palm Jumeirah[21] – or creating brands from hitherto unchartered territory – such as art, as Aldar has done in Abu Dhabi with the Louvre apartments.[22]

These attributes are not confined to services. Accompanying product offers for luxury apartments are not new, but the assignation of distinctive or unique products from the branding partner is a characteristic now associated with branded residences. For example, again in Miami, Aston Martin offered a rare new model with the penthouse of their residences there.[23] This process also is set to expand and eventually trickle down to lower levels of luxury.

What is now problematic for developers and buyers alike is the absence of any comprehensive list of such services and products, let alone a rating system for branded residences that might parallel the evolving international system of hotel ratings.[24] In the absence of such a system, developers rely on advice – which relies on analysis based on comprehensive data – to navigate their way through the negotiation process with branding partners.

“Competition in the branded residence market is intensifying at both national and city levels. While Dubai remains a leader, cities like Riyadh, with Elie Saab and Ritz Carlton, and Muscat, with Mandarin Oriental, are entering this dynamic space. To stay competitive, developers must continually innovate, offering features like private beaches, as seen with Armani in Palm Jumeirah, or unique concepts, such as Aldar’s Louvre Apartments in Abu Dhabi.”

Hassan Alladin

Manager, Strategy and Consulting

Conclusion

The era of branded residences is clearly upon us. But we can draw parallels with the early days of LEED and other sustainability criteria where not all green buildings were profitable for developers or investors. Branded residences have so far demonstrated both opportunity and resilience but there are clearly risks for both developers and investors that are being overlooked amid headlines that claim large premia. Where careful definitions and reliable analytical methods are not employed, there is a clear danger that the headlines do not present an accurate picture of actual branded residence premia. Even when they do reach an accurate estimate of benefits, developers must compare the costs of their agreements and assessment of branding as a project-with-a-project. There will be optimal routes through an increasingly complex maze of decision-making for developers and investors that branded residences now present, but only by relying on data-driven decision-making that can pinpoint the actual contribution of the brand to the financial returns of this new asset class.

[1] Foster, R Daniel (2024, May 15) Branded Residences: A Triple Win For Developers, Brands And Buyers. Forbes.

[2] Frost, J. (2022, February 16) Immerse yourself in the Disney Lifestyle – Introducing Storyliving by Disney Residential Communities. https://thedisneyblog.com/2022/02/16/immerse-yourself-in-the-disney-lifestyle-introducing-storyliving-by-disney-residential-communities/.

[3] Sands, R. (2024, May 6) Inside A $32 Million Cipriani Residences Penthouse In Miami. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rogersands/2024/05/04/inside-a-32-million-cipriani-residences-penthouse-in-miami/.

[4] Peacock, A. (2024, 29 July). John Lewis set to build its first housing development in London. Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2024/07/29/john-lewis-partnership-first-housing-development-london/.

[5] Lloyds Banking Group (2021, 7 July) Lloyds Banking Group moves into the private rental sector with launch of Citra living. https://www.lloydsbankinggroup.com/media/press-releases/2021/lloyds-banking-group/lloyds-banking-group-moves-into-the-private-rental-sector-with-l.html.

[6] Haigh, R. (2021, 26 January). How We Value the Brands in Our Annual Rankings. Brand Finance. https://brandfinance.com/insights/methodology-brands-annual-rankings

[7] Kantar (2024) Global. Discover the world’s most valuable brands. https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/brandz/global

[8] Interbrand (2022) Brand Valuation. https://interbrand.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IB-Brand-Valuation_220608.pdf

[9] Jochinke, Z. (2024, 16 October) Unveiling Market Trends: Insights into Branded Residences FHS World. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9V3T17gWB8o.

[10] CW Property (2024, January 17) Dar Al Arkan, Elie Saab launch branded residences in Riyadh. https://property.constructionweekonline.com/dar-al-arkan-elie-saab-riyadh/

[11] Diriyah (2024) The Ritz-Carlton Residences. https://www.diriyahcompany.sa/en/diriyah-living/ritz-carlton.

[12] Inspirations (2023, December 27) Top 15 Branded Residences in Saudi Arabia. https://www.themostexpensivehomes.com/luxe-living/top-15-branded-residences-in-saudi-arabia/

[13] Mandarin Oriental (2024) Muscat. https://www.mandarinoriental.com/en/residences/current/muscat.

[14] Hotelier India (2024) The Rise of Branded Residences. https://www.hotelierindia.com/development/the-rise-of-branded-residences

[15] Hotelworks (2024, February) Philippines: A Rising Hub for Branded Residences Investment Property Buyers. https://www.c9hotelworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/2024-02-philippines-branded-residences-market-update.pdf

[16] W Capital (2024, June 26) The top 10 nationalities buying property in Dubai in H1 2024. Zawya.com. https://www.zawya.com/en/press-release/research-and-studies/the-top-10-nationalities-buying-property-in-dubai-in-h1-2024-emdsc4va.

[17] Kassam, A., Gupta, K. and Chesworth, R. (2024, October) Shifting Sands. The GCC’s Equity Market Transformation. https://www.ssga.com/library-content/assets/pdf/global/equities/2024/shifiting-sands-gcc-equity-market-transformation.pdf.

[18] Cheema-Fox, A. and Greenwood, R. (2024) How do Global Portfolio Investors Hedge Currency Risk? https://globalmarkets.statestreet.com/research/service/public/v1/article/insights/pdf/v2/a01c79b7-23cb-40cb-b02b-3c2d80ebefa2/how_do_global_portfolio_investors_hedge_currency_risk.pdf.

[19] AMG Realty (2024) The Dezervator. https://porschetowermiami.net/the-dezervator/

[20] Mousavi, E. (2023, February 7) What are Branded Residences? https://elitetraveler.com/property/what-are-branded-residences.

[21] Armani Group (2024) Armani Beach Residences Palm Jumeirah. https://armaniresidencesdubaipalm.com/.

[22] Aldar (2022, 16 March). World’s first Louvre branded residences to bring culturally-inspired way of living to Abu Dhabi. https://cdn.aldar.com/-/media/project/aldar-tenant/aldar2/images/press-releases/press-release—louvre-abu-dhabi-residences-by-aldar—final-16032022_eng.pdf?rev=-1

[23] Hensley, B. (2021, 4 June) Tuck in at the New Aston Martin Residences in Miami. https://elitetraveler.com/cars-jets-and-yachts/cars/tuck-in-with-aston-martin-residences-miami

[24] Cavendish Maxwell (2024, 9 October) Is the hotel rating system still fit for purpose? https://cavendishmaxwell.com/insights/opinion/is-the-system-of-hotel-rating-still-fit-for-purpose.