Interest rates, lending and the real estate market

What has happened

Responding swiftly to the cut in interest rates by the US Federal Reserve, the UAE central bank followed suit in September this year with a reduction of 25 basis points to 2.25%. This is far from a historic low: interest rates in the UAE averaged 1.43% from 2007 until 2019, reaching an all-time high of 4.75% in November 2007 and a record low of 1% in January 2009 as policymakers attempted to cope with the global financial crisis[1]. The UAE was not alone: the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority also lowered its repo rate from 2.75% to 2.5%. This reversed a trend of rising rates since 2015: UAE homeowners with Eibor-based mortgages had hitherto experienced nine rate hikes then, when rates rose by 0.25% to 1%, with continued increases until the end of 2018 before a reversal this year.

What effect on the real estate market can we now expect from interest rate cuts?

What the theory says

Finance theory (notably the Pasquale-Wheaton four quadrant approach[2]) says that real estate assets, even housing, are valued essentially as a stream of potential income – rather like a corporate bond or an equity, and unlike gold or diamonds. The future cashflows from the asset are discounted at a cost of capital which reflects, amongst other things, both inflation and real interest rates. For domestic investors, this is theorised as the risk-free rate, plus a risk premium.

The risk-free rate, being referenced to the cost of government borrowing, falls when interest rates are cut. If the assumption is made that the rise in the risk premium caused by an increase in future projected share prices is offset by the increase in rents that the real estate asset will generate, then the lowering of the risk-free rate is a windfall gain to the investor, which will result in a rise in real estate prices across the market, measured by a fall in cap rates, which bear a close relationship theoretically to the market discount rate.

Market analysts often assume that the theory is correct. Borrowing becomes cheaper for investors and potential homebuyers, capital inflows can be expected from other countries, local stock markets respond positively, domestic bonds rise in value and even tourism becomes more attractive.

The currency effect of lower interest rates

Nothing comes without a cost, and the potential disadvantage of cutting interest rates was always considered to be the impact on the domestic currency. So, the definite winners from a cut in USD and local interest rates will generally be those who account in USD as they do not face this exchange rate risk.

For those who account in other currencies, the relative impact of currency versus borrowing costs will determine the extent to which they benefit. At present, with the advantage of a couple of months’ hindsight, it does seem as if the benefits will outweigh any disadvantages, as the USD has not fallen. In fact, looking at a basket of other currencies, quite the opposite for the dollar index: 91.49 on June 7 and 92.52 on September 13[3]. If US policymakers intend to drive down the dollar, they will have to look elsewhere than modest interest rate cuts to do so.

This may have important implications for real estate markets, both in the USA and in those countries with exchange rates pegged to the dollar. Investors who based on the theory might have been reluctant to invest in such countries but would certainly have benefitted over the past year had they ignored its implications: as Cavendish Maxwell’s Currency Adjusted Real Estate Indices have demonstrated, viewed in currencies other than the USD, returns in the UAE and elsewhere in the region have held up extremely well.

What does the evidence tell us?

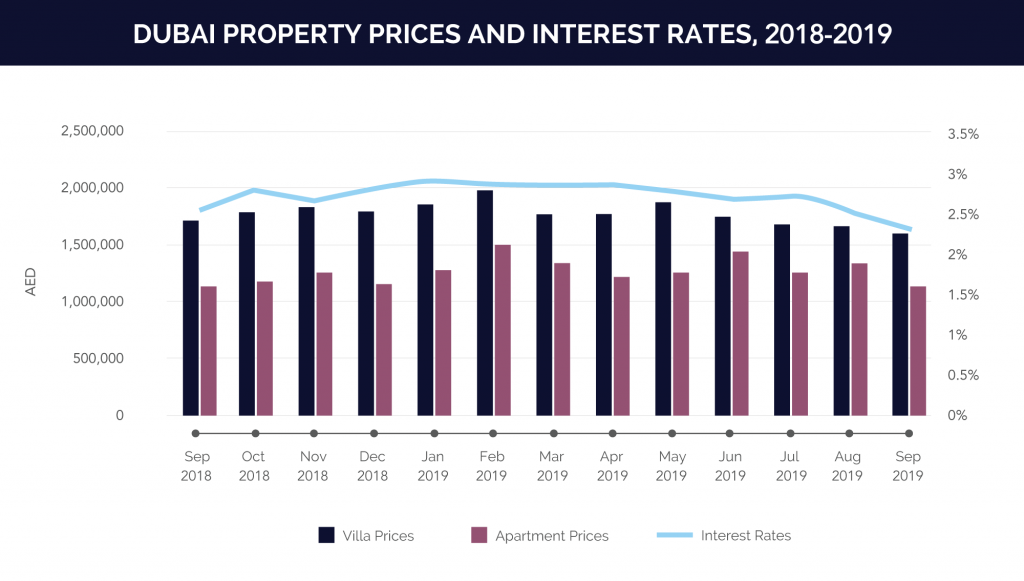

It is quite clear that, at least in the short term, the cut in interest rates has not fed through into higher real estate prices. Here is the evidence from Dubai:

Professional opinion from central bankers does however suggest that maximum impact from interest rate cuts takes between one to two years to have an effect[4]. Partly, this is because many borrowers, including in the UAE, are on fixed term rates, at least over two to three years. An immediate rise in real estate prices should not therefore be expected. If the theory is correct, investors should jump in now.

A changed paradigm for interest rates?

There may, however, be much more important reasons why the UAE real estate market has not responded to an interest rate cut.

Firstly, modest cuts at current low levels of interest rates might well not be crucial to investors’ decision-making when their spending envelopes are not stretched. Interest rates may have to rise back to double-digits and lending ratios remain unchanged before this starts to take effect again. If an investor is proposing a house purchase with a USD 500,000 mortgage over 12 years, for example, the effect of raising interest rates from 1% even to 3% is just over USD 450/month. For a rate cut of 25 basis points, the benefit is under USD 60/month. If a 2% rise in interest rates over three years might be expected to have some significant impact, both on discretionary spending and on real estate investment, a 0.25% cut is certainly not likely to be enough to reverse the trend. These numbers are just not sufficient to pull a market out of recession, especially when bank margins will also be hurt by interest rate cuts, and policymakers will always have to strike a balance between the interests of borrowers and those of savers. Technical correlations over such a short time-frame may not tell us much, but whilst for villas it is 0.75, for apartments the figure is only 0.47, yet it is certainly hard to believe that villas are more levered than apartments, or that their occupants are more exposed to small interest rate changes.

Secondly, and linked to the first, market dynamics are therefore determined by much larger issues. the issue of competitive jurisdictions is also relevant to investment in any one real estate market. A successful Expo 2020, and regional political stability, are likely to be far more important determinants of the market than modest changes in interest rates. So too, whilst it may be true that the Reserve Bank of Australia can reasonably predict a positive market impact from an interest rate cut, at least in Sydney and Melbourne, as internal demand generates prices, just as it is the case in Riyadh and Jeddah, that is not true in Abu Dhabi or Dubai any more than in Perth[5], three cities where the real estate market is heavily influenced by investment from abroad, and the importance of population growth, FDI and attendant GDP growth is paramount. This may suggest a different elasticity of response to interest rates in Saudi Arabia than in the UAE.

Thirdly, and of most concern to policymakers, the theory that a reduction in interest rates raises real estate prices by increasing the present discounted value of the asset’s future income flows might no longer be correct. There are, in turn, two possible reasons for this. One is that discounted value analysis may no longer be the main way that real estate markets, including housing, are valued in an urban setting. As yields fall and real estate becomes increasingly valuable for its store-of-value rather than future cashflow, this is in fact almost inevitable. The second is that if the negative signalling effect of lowering interest rates outweighs the positive effect of lower real borrowing costs, the efforts of central banks might be futile. If this be true, central banks and policymakers are running out of options. Low interest rates and even quantitative easing may lend a temporary boost to asset prices but neither do anything to reinflate consumer demand or promote confidence.

Conclusion

The facts support the contention that theory designed more than two decades ago based on evidence from markets dominated by domestic investors may not apply to the UAE. If so, real estate markets in the UAE may not be as elastic in the short term with respect to modest interest rate cuts as policymakers might wish. On the other hand, investors in the market for the long-term might reasonably conclude that the performance of the UAE market over the past three years does not primarily rest on progressive interest rate rises. They should therefore draw two conclusions. First, even if the UAE authorities continue to cut rates, in response to similar actions from the Fed, they should not expect windfall gains as a result, even if the USD and therefore the AED hold up in value despite the cuts. But secondly, they could reasonably be encouraged by expecting a similarly flat response to interest rate increases in the future.

Overall, as the Western world threatens to imitate Japan in permanent sluggish growth, and both fiscal and monetary policy loses its grip on economic demand worldwide, real estate investors are surely right to balance their portfolios with exposure to emerging markets, including both BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and individual locations of excellence.

[1] https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/united-arab-emirates/short-term-interest-rate

[2] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1540-6229.00579

[3] https://ycharts.com/indicators/trade_weighted_us_dollar_index_major_currencies

[4] https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2017/sep/1.html

[5] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-06-05/how-will-rba-interest-rate-cut-affect-perth-property-market/11178150