Mortgages vs Payment Plans – What is the better pick?

Buy with a mortgage

In most parts of the world, developers have insufficient size and financial ability to provide financial support to residential real estate purchasers. Instead, banks and other financial institutions provide mortgages for those unable, or unwilling, to make purchases in cash. In the UAE, mortgages are limited to a loan-to-value ratio of 80% (for citizens), and 75% (for expatriates) for all purchases of first home residential properties up to AED 5 million, and 70% and 65%, respectively, for properties over AED 5 million. Second and subsequent properties have more stringent lending criteria and off-plan purchases are limited to 50% mortgages. Costs such as the 4% Dubai Land Department Fees and 2% Agency Fees must also be paid by the borrower.

Buy with a payment plan

Alternatively, the borrower can take the payment plan on offer from the developer. Cavendish Maxwell has a detailed database on the wide variety of payment plans that are available and the subtleties of the resultant cash flows, but for transparency I have taken the simple example noted in a publicly available article by property consultant Mohamed Zidan[1]. The plan he identified, from developer Deyaar located in the IMPZ project, offered 10% payable on signature, 10% on handover, and 80% over 60 months. Let’s assume that the handover was a year after the signature. The numerical results would, of course, differ if we made different assumptions about both the payment plan and the mortgage, but the principles of comparative assessment remain the same.

Making economic sense of the choice

In theory, the choice revolves around two questions. First, which organisation has the lower cost of capital. If a bank is able to fund itself, whether through debt, equity, or a combination, at a lower cost than a developer, or vice versa, then all other things being equal, the mortgage option will be less expensive for the customer. Second, the relative profit margin being taken by the bank versus the developer from their financing. If they both forecast the same financial return from their financial activities, then the cost to the borrower should be identical. No free lunch.

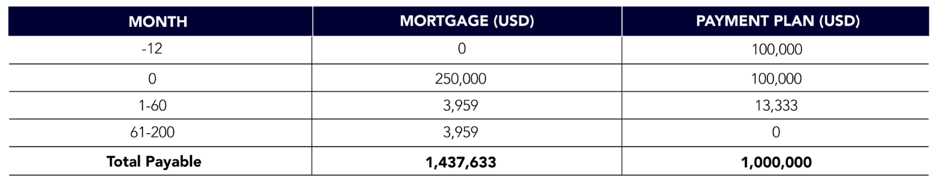

In practice, this is never likely to be the case, for both economic and regulatory reasons. Economically, in reality, borrowers differ in their own cost of capital. A simple spreadsheet serves to demonstrate the consequences if they do not. Our hypothetical borrower is purchasing a USD 1 million apartment and has two possible financing options to choose from. On the one hand, there is an offer from a bank of a 25-year mortgage – the longest term available in the UAE – at a constant interest rate of 4%, and on the other, the Deyaar payment plan. If they take this offer, the borrower, who we will assume is an expatriate, must come up with a 25% deposit. The remaining 75%, which is USD 750,000, is paid off with monthly payments of USD 3,959. The table shows the different cash flows out from the purchaser:

At first glance, the payment plan option would appear vastly superior. Who would not prefer paying almost a third less for the identical property? But now, let the spreadsheet tell us what would happen if the borrower assumed a 10% cost of capital for themselves. Another way of putting this is to say that every dollar the borrower pays towards the property is going to cost the purchaser 10% every year. A still further way is to suggest that the opportunity cost of putting money into the apartment is to lose out on 10% annual returns spread across other markets. Now what does the choice look like? The table shown below now tells a very different story:

The analysis above has been done annually but upgrading to monthly would show only relatively minor differences. The numbers in red include the full cost to the borrower over 25 years, although only the seven covering the payment plan have been shown in the extract. The time ‘now’ is Year -1, when the choice is to be made. The discount rate of 10% for every year is a direct reflection of the borrower’s opportunity cost of capital. Effectively it is saying this: if the borrower had the difference between the mortgage cost and the developer payment plan and was able to invest that difference at 10% every year, viewed over a 25-year period, what would the difference look like? And the answer is, around USD 123,000, which is a massive difference considering the initial purchase price is just USD 1 million.

The reason for the difference is the postponement of payments with the mortgage by comparison to the payment plan. But the analysis above only works in favour of the mortgage when the reinvestment (discount) rate of the borrower is greater than the cost of the mortgage. If the borrower could only reinvest at 2%, then the result looks quite opposite:

Now, a gap of USD 217,000 opens up in the opposite direction. In the absence of an effective alternative investment strategy, the borrower would be much better advised to take advantage of the offer available from the developer and cut drastically their required payments in the future. Ultimately as we know, if that rate reduces to zero, the difference is back to the USD 438,000 of simple cash difference between the two approaches.

This analysis assumes unchanging interest rates. Interest rates for variable mortgages are frequently linked to EIBOR[2], but this can and does vary significantly. If borrowers end up paying much higher interest rates in the future – and the risk curve is almost certainly in that direction – then the payment plan option may well gain additional traction. It also ignores a range of issues that will affect cash flow, from capital gains to taxation and administrative costs. As such it can only be an indication of logical choice, not a firm guide to action.

There are more issues to consider too. As developers themselves borrow from banks and bondholders, all developer payment plans do is put an extra layer of administration between the borrower and the financial institutions. Eventually, therefore, economics would suggest they will disappear. However, there are also numerous practical and administrative issues to consider. Often cited is the imperfection of the mortgage market: some borrowers may either not be able to obtain mortgages or may not choose to do so. Yet the illogicality of any mortgage market whereby borrowers can find the much higher levels of monthly payment required to meet the developer payment plan criteria, but are yet unable to meet regulatory or other lending criteria for longer-term mortgage plans with far lower levels of monthly payments, does sit oddly to anyone familiar with a Western market. Although payment plans are familiar in markets such as Cyprus, in London, for example, developer payment plans are virtually unknown, not only because of the effectiveness of the mortgage market and the dominance of salaried borrowers over cash transfers, but because the level of monthly payments required would be beyond the majority of even well-heeled potential purchasers, at least those on salaries and living locally. Even if a present bias has been observed in mortgage markets in developed countries[3] included, resistance to long-term commitments is also likely to gradually diminish as more people become aware of the arguments for the opportunity cost of finance. Arguably at least, behavioural finance has as much to contribute in terms of solving the debate between mortgages and payment plans as traditional economic analysis.

This argument also applies to those payment plans in the UAE that are a way of extending the credit rating of the developer to purchasers, e.g. by offering them a 50% 25-year mortgage after completion – the issue of where that initial half of the purchase price is to come from remains to be addressed. Secondly, there are all the market forecast, flipping and transfer issues to consider. Thirdly, there may be capital allocation questions by developers to consider: under current conditions they may actually prefer to act as lenders, at least partially, rather than concentrate purely on expanding their development operations.

Conclusions

If markets are working perfectly, all borrowers are created not only equal to each other, but to developers and banks in their capacity to borrow and avail the same rates of interest. If so, then there is no benefit to be gained from either strategy. It is only when market imperfections creep in that comparative analysis of the strategies is beneficial. In current UAE market conditions, where developers can borrow as cheaply as banks in many cases, and when discount rates are very low along with inflation and projected returns, the economic case for payment plans becomes stronger. Developers will emerge, as they have done, as real competitors to mortgage providers. The limits to their success, however, lie in the still very considerable monthly payments that they demand from their purchasers. As payment plans stretch out to 10 years or more, developers will find themselves under pressure from their own bondholders – who want the higher returns of development by comparison to long-term lending – and corporate lenders to divest themselves of their financial departments and subsidiaries. Some may emerge as financial institutions in their own right; others may be taken over by leading banks both local and international. Either way, at that point, we will have come full circle. The question for now though is, how long will that process take?

[1] Zidan, M. (2019) Top 5 payment plan projects in Dubai 2019. Available at: https://www.zidan-dxb.com/top-5-payment-plan-projects-dubai-2019/ Retrieved 5 January 2020.

[2] https://www.centralbank.ae/en/services/eibor-prices Retrieved 5 January 2020

[3] Atlas, S.A. et al (2014) Time Preferences and Mortgage Choice. Available at: https://faculty.fuqua.duke.edu/~jpayne/bio/Time%20Preferences%20and%20Mortgage%20Choice%20-%207-31-14.pdf Retrieved 5 January 2020.